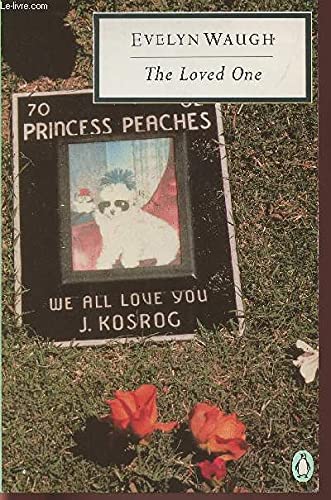

The unfinished yet gracefully rounded tale “Work Suspended,” for instance, which consumes eighty-four pages of the present book, feels almost a match for “The Loved One,” “Helena,” and “The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold”-the brisk, peppery, death-haunted trio of novellas that Waugh produced in his riper years, and which are available only in individual volumes. The title is clear, although in the Waugh canon a short story is not easily defined.

Best of all, we have a fresh gathering of primary material: “The Complete Stories of Evelyn Waugh” (Little, Brown 29.95). We have had biographies in two volumes from Martin Stannard and in one volume from Selina Hastings more recent, and more slender still, is David Wykes’s “Evelyn Waugh: A Literary Life,” which bravely introduces us to the new adjective “Wavian”-helpful to scholars, perhaps, but unlikely to gain a wider currency. The years since Waugh’s death, in 1966-and, in particular, the past decade-have been marked by studious attempts to savor his achievements.

The hint is clear enough: Waugh, and Waugh alone, was of vintage stuff. Now, thirty years later, he would sit in solitude, grasping his glass, bullishly proud that there was nobody present who deserved to share a drop. At Oxford in the nineteen-twenties, Waugh had chosen his friends on the basis of their ability to handle, or entertainingly mishandle, the effects of alcohol “an excess of wine nauseated him and this made an insurmountable barrier between us,” he wrote of one college acquaintance. In anticipation of the event, he wrote to a friend, Brian Franks, with a description of the menu, closing with the words “Non Vintage champagne for all but me.” Rarely has an edict been issued with such a firm smack of the lips, yet nothing could be sadder. In July, 1956, Evelyn Waugh gave a dinner party for his daughter Teresa.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)